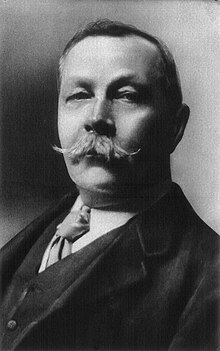

About the Author: Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born on 22 May 1859 at 11 Picardy Place, Edinburgh, Scotland. From 1876 to 1881, he studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, including a period working in the town of Aston (now a district of Birmingham) and in Sheffield, as well as in Shropshire at Ruyton-XI-Towns. While studying, Doyle began writing short stories. His earliest extant fiction, "The Haunted Grange of Goresthorpe", was unsuccessfully submitted to Blackwood's Magazine. His first published piece "The Mystery of Sasassa Valley", a story set in South Africa, was printed in Chambers's Edinburgh Journal on 6 September 1879. On 20 September 1879, he published his first non-fiction article, "Gelsemium as a Poison" in the British Medical Journal. In 1882 he joined former classmate George Turnavine Budd as his partner at a medical practice in Plymouth, but their relationship proved difficult, and Doyle soon left to set up an independent practice. Arriving in Portsmouth in June of that year with less than £10 (£900 today) to his name, he set up a medical practice at 1 Bush Villas in Elm Grove, Southsea. The practice was initially not very successful. While waiting for patients, Doyle again began writing stories and composed his first novels, The Mystery of Cloomber, not published until 1888, and the unfinished Narrative of John Smith, which would go unpublished until 2011. He amassed a portfolio of short stories including "The Captain of the Pole-Star" and "J. Habakuk Jephson's Statement", both inspired by Doyle's time at sea, the latter of which popularized the mystery of the Mary Celeste and added fictional details such as the perfect condition of the ship (which had actually taken on water by the time it was discovered) and its boats remaining on board (the one boat was in fact missing) that have come to dominate popular accounts of the incident. Doyle struggled to find a publisher for his work. His first significant piece, A Study in Scarlet, was taken by Ward Lock Co. on 20 November 1886, giving Doyle £25 for all rights to the story. The piece appeared later that year in the Beeton's Christmas Annual and received good reviews in The Scotsman and the Glasgow Herald. The story featured the first appearance of Watson and Sherlock Holmes, partially modeled after his former university teacher Joseph Bell. Doyle wrote to him, "It is most certainly to you that I owe Sherlock Holmes ... Round the center of deduction and inference and observation which I have heard you inculcate I have tried to build up a man." Robert Louis Stevenson was able, even in faraway Samoa, to recognize the strong similarity between Joseph Bell and Sherlock Holmes: "My compliments on your very ingenious and very interesting adventures of Sherlock Holmes. ... Can this be my old friend Joe Bell?" Other authors sometimes suggest additional influences—for instance, the famous Edgar Allan Poe character C. Auguste Dupin. A sequel to A Study in Scarlet was commissioned and The Sign of the Four appeared in Lippincott's Magazine in February 1890, under agreement with the Ward Lock company. Doyle felt grievously exploited by Ward Lock as an author new to the publishing world and he left them. Short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes were published in the Strand Magazine. Doyle first began to write for the 'Strand' from his home at 2 Upper Wimpole Street, now marked by a memorial plaque. In this period, however, Holmes was not his sole subject and in 1893, he collaborated with J.M. Barrie on the libretto of Jane Annie. Doyle was found clutching his chest in the hall of Windlesham Manor, his house in Crowborough, East Sussex, on 7 July 1930. He died of a heart attack at the age of 71. His last words were directed toward his wife: "You are wonderful." At the time of his death, there was some controversy concerning his burial place, as he was avowedly not a Christian, considering himself a Spiritualist. He was first buried on 11 July 1930 in Windlesham rose garden. He was later reinterred together with his wife in Minstead churchyard in the New Forest, Hampshire. Carved wooden tablets to his memory and to the memory of his wife are held privately and are inaccessible to the public. That inscription reads, "Blade straight / Steel true / Arthur Conan Doyle / Born May 22nd 1859 / Passed On 7th July 1930." The epitaph on his gravestone in the churchyard reads, in part: "Steel true/Blade straight/Arthur Conan Doyle/Knight/Patriot, Physician, and man of letters". Undershaw, the home near Hindhead, Haslemere, south of London, that Doyle had built and lived in between October 1897 and September 1907, was a hotel and restaurant from 1924 until 2004. It was then bought by a developer and stood empty while conservationists and Doyle fans fought to preserve it. In 2012 the High Court ruled that the redevelopment permission be quashed because proper procedure had not been followed. A statue honours Doyle at Crowborough Cross in Crowborough, where he lived for 23 years. There is also a statue of Sherlock Holmes in Picardy Place, Edinburgh, close to the house where Doyle was born.

My Review: In this story, Dr. Watson receives a letter, which he then refers to Holmes, from Percy Phelps, a former schoolmate who is now a Foreign Office employee from Woking and has had an important naval treaty stolen from his office. It disappeared while Phelps had stepped out of his office momentarily late in the evening to see about some coffee that he had ordered. His office has two entrances, each joined by a stairway to a single landing. The commissionaire kept watch at the main entrance. There was no-one watching at the side entrance. Phelps also knew that his fiancée's brother was in town and that he might drop by. Phelps was alone in the office.

Phelps pulled the bell cord in his office to summon the commissionaire, and to his surprise the commissionaire's wife came up instead. He worked at copying the treaty that he had been given while he waited. At last, he went to see the commissionaire when it had taken some time for the coffee to arrive. He found him asleep with the kettle boiling furiously. He did not need to wake him up, however, as just then, the bell linked to his office rang. Realizing that someone was in his office with the treaty spread out on his desk, Phelps rushed back up and found that the document had vanished, and so had the thief.

It seemed obvious that the thief had come in through the side entrance; otherwise he would have passed Phelps on the stairs at some point, and there were no hiding places in his office. No footprints were seen in the office despite its being a rainy evening. The only suspect at that point was the commissionaire's wife, who had quickly hurried out of the building at about that same time.

This was followed up, but no treaty was found with her. Other suspects were the commissionaire himself and Phelps's colleague Charles Gorot. Neither seemed a very likely suspect, but the police followed them both, and the commissionaire's wife. As expected, nothing came of it.

Phelps was driven to despair by the incident, and when he got back to Woking, he was immediately put to bed in his fiancée's brother's room. There he remained, sick with “brain fever” for more than two months, his reputation and honour apparently gone, and his career in dire jeopardy.

Holmes is quite interested in this case, and makes a number of observations that others seem to have missed. The absence of footprints, for instance, might indicate that the thief came by cab. There is also the remarkable fact that the dire consequences that ought to result from such a treaty being divulged to a foreign government have not happened in all the time that Phelps has been ill. Why was the bell rung?

Holmes gathers some useful information at Briarbrae, the Phelps house, where his fiancée, Annie Harrison, and her brother Joseph have also been staying. She has been nursing him days while a nurse has been employed to keep watch over him at night. Joseph, it seems, is along for the ride.

After seeing Phelps at Woking, Holmes makes some inquiries in town. He visits Lord Holdhurst, Phelps's uncle, who gave his nephew his important job with the treaty, but Holmes dismisses him as a suspect, and is quite sure now that no-one could have overheard their discussion about the job. Lord Holdhurst reveals to Holmes the potentially disastrous consequences that might occur if the treaty should fall into the hands of the French or Russian embassies. Fortunately, nothing has yet happened, despite the many weeks since the theft. Apparently, the thief has not yet sold the treaty, and Lord Holdhurst informs Holmes that the villain's time is running out, as the treaty will soon cease to be a secret. Why, then, has the thief not sold the treaty?

Holmes returns to Woking, not having given up, but having to report that no treaty has turned up yet. Meanwhile, something interesting has happened at Briarbrae: someone tried to break in during the night, into Phelps's sick room, no less. Phelps surprised him at the window but could not see his face through the hooded cloak that he was wearing. He did, however, see the interloper's knife as he dashed away. This happened the very first night that Phelps felt he could do without the nurse.

Unknown to anyone else at this point — although Watson infers it from his friend's taciturnity — Holmes knows what is going on. He orders Annie to stay in her fiancé's sick room all day, and then to leave it and lock it from the outside when she finally goes to bed. This she does.

Holmes finds a hiding place near Briarbrae to keep watch after having sent Watson and Phelps to London on the train, and also letting the occupants at Briarbrae believe that he intended to go with them, ostensibly to keep Phelps out of harm's way should the interloper come back.

Holmes waits until about two o'clock in the morning, and the interloper appears — out of the house's tradesman's entrance. He goes to the window, gets it open as before, opens a hidden hatch in the floor, and pulls out the treaty. He then steps straight back out the window into Holmes's hands.

The treaty has been in Phelps's sick room all the time, while the thief, Joseph, who usually slept in that room, could not get to it. He rang the bell in Phelps's office after dropping by to visit and finding him not there, but then he saw the treaty and its potential value. His inability to reach the treaty explains why there have been no dire political consequences. Holmes explains that Joseph had lost a great deal of money on the stock market, which explains his need for money. Being a very desperate and selfish man, he cared nothing for the consequences Phelps might suffer from the document's loss.

Always one with a flair for the dramatic, Holmes literally has the treaty served up to Phelps as breakfast the next morning at 221B Baker Street, where he has spent the night under Watson's watchful eyes (although there has been no danger). Phelps is ecstatic, Holmes is quietly triumphant, and once again, Watson is dumbfounded.

Holmes explains that several clues all pointed to Joseph: the fact that the thief knew the ways of the office well, given that he had rung the bell before seeing the treaty, and that Phelps mentioned his relatives had been shown around; the fact that Joseph had intended to stop in and see Phelps on his way home, and that the theft had been committed very soon before the train would depart for Woking; that the thief had come in a cab, given that it was a rainy night but that there were no wet footprints in the passage; and the fact that the burglar who tried to break into Phelps's room was familiar with the layout of the house.

Excellent plot, I recommend this book to all Sherlock Holmes fans and any reader in general that enjoys a very well written mystery story.

If you read this review, feel free to leave a comment.

No comments:

Post a Comment